A Trip to the American Civil Rights South

On this trip sponsored by “The Nation” magazine, my wife and I traveled by bus over eight days to four states we had never visited before, didn’t sleep much, learned a ton, ate mostly fried food, got to know 27 traveling companions, and met with individuals at each stop who told us very personal stories about their experiences with racism.

What we saw was unforgettable and unforgivable.

Sunday / Monday - Jackson, Mississippi

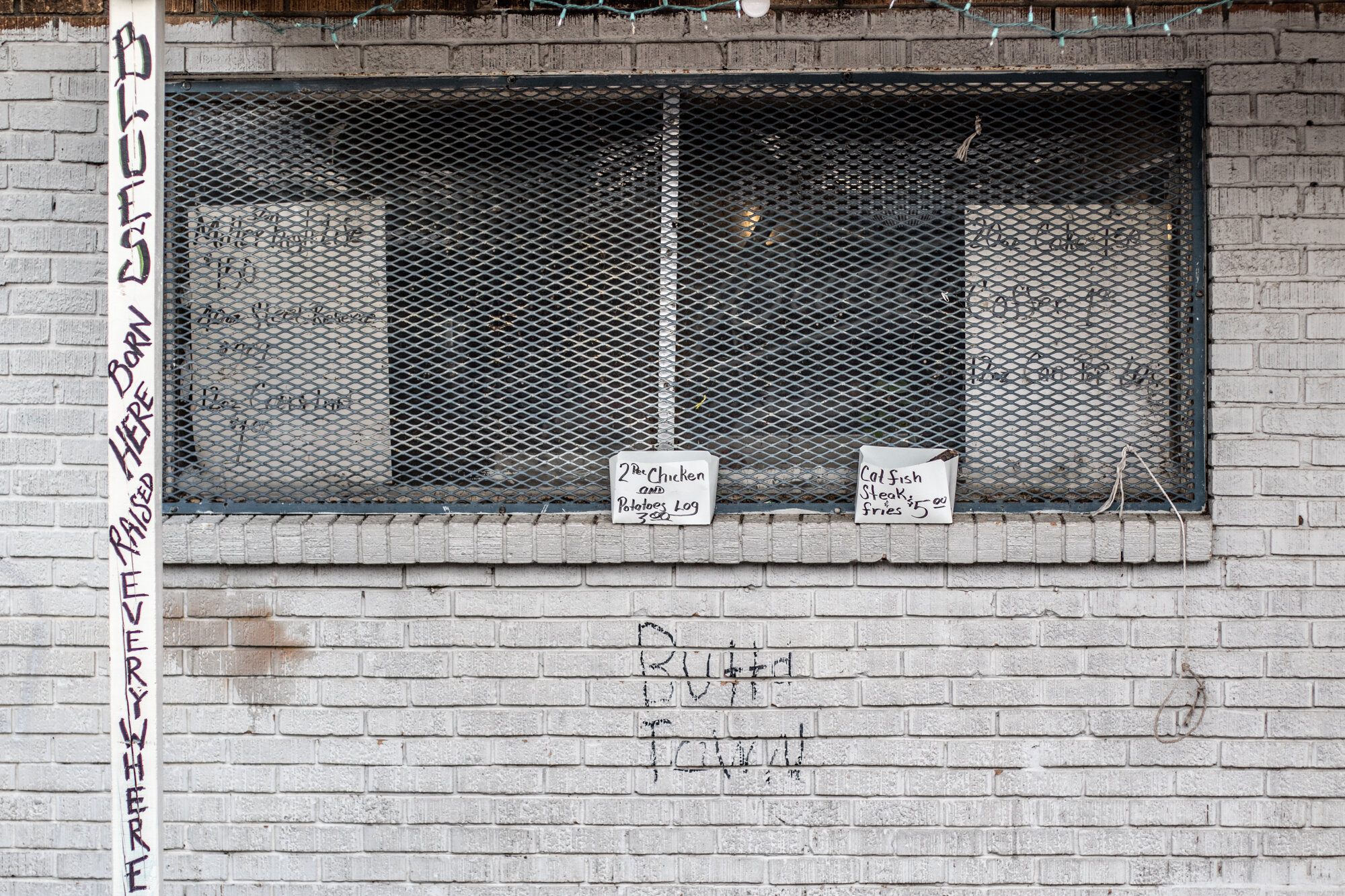

Farish Street was once the thriving center of African American life in Jackson during the Jim Crow era. Now there are boarded-up buildings and vacant lots, though a few businesses struggle to survive.

We, along with friends whom we knew from a previous trip, arrived the night before The Nation tour started and decided to go to the Greater Bethlehem Temple Church in Jackson for Sunday services. We were very warmly welcomed into a truly inspiring worship service filled with music (a 50-person choir and five-piece band), a sermon, offerings, and an outpouring of Hallelujahs and Amens.

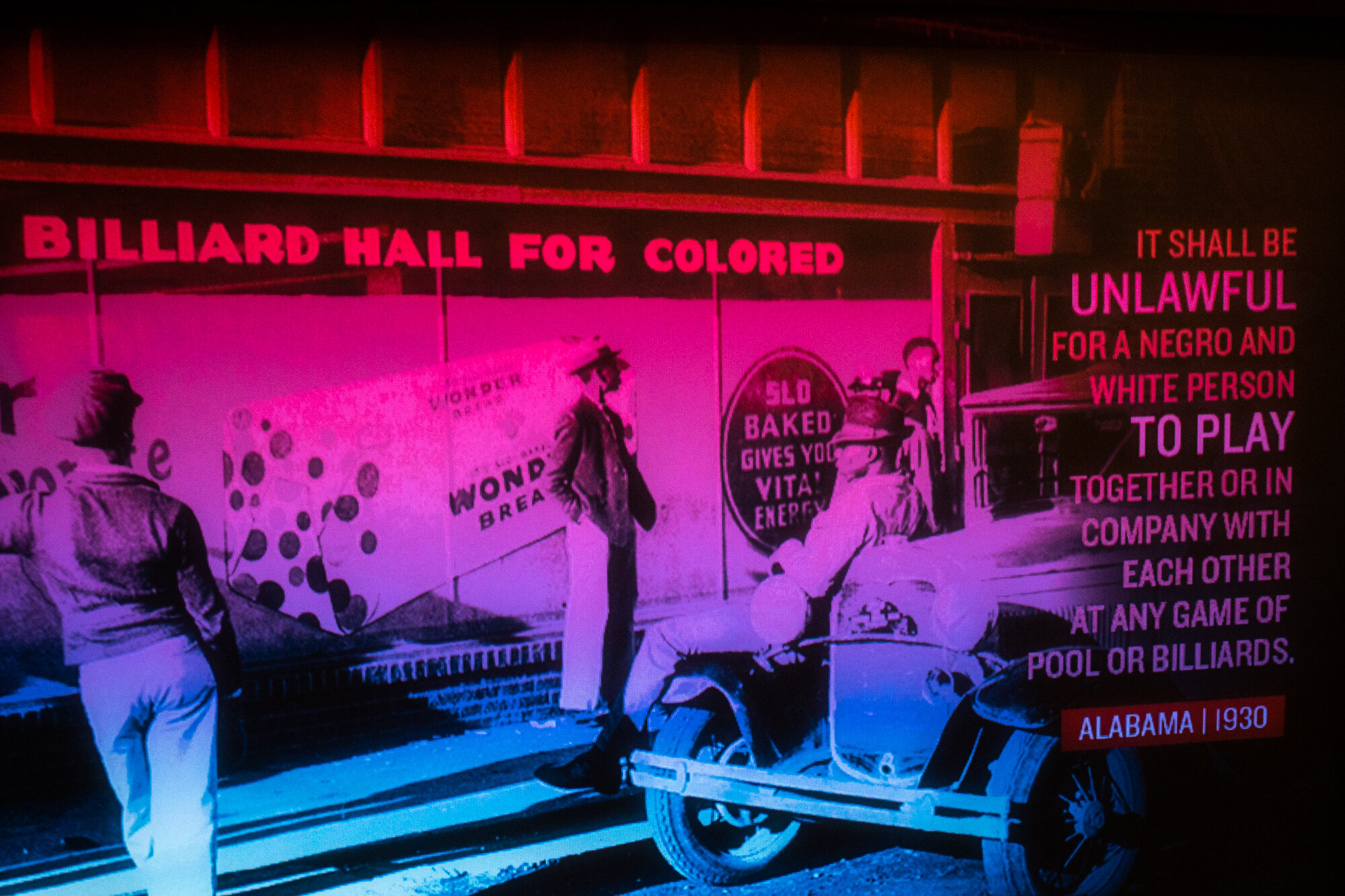

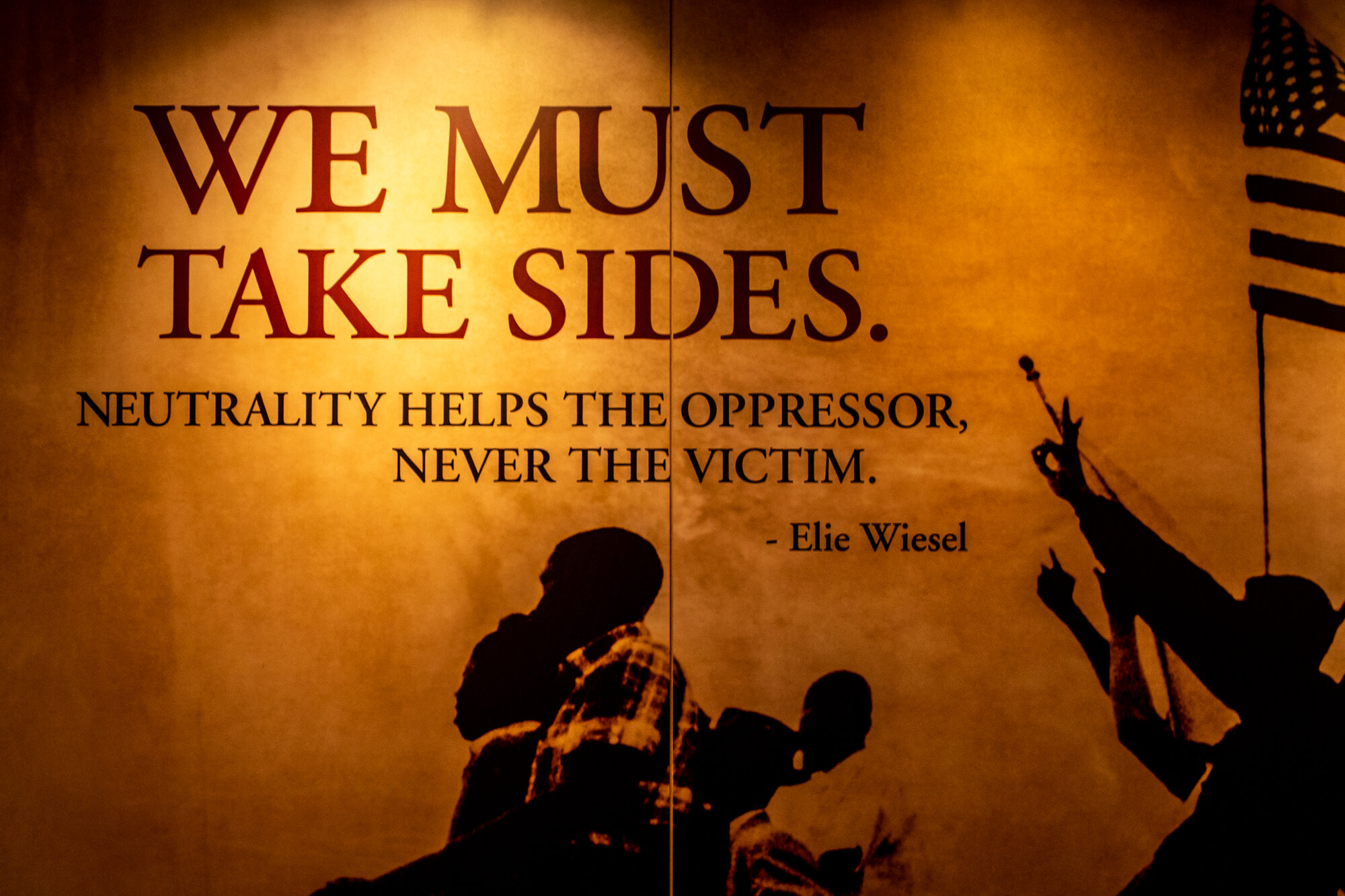

After joining the group, we walked to the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, which opened in 2017 and which has no flagpole out front, because the state flag had a Confederate symbol in it. Eight interactive galleries that show the systematic oppression of black Mississippians and their fight for equality branch off of a rotunda playing music of the Movement. (A sign of progress: In 2020, Mississippi lawmakers voted to abolish their state flag that has flown for 126 years.)

At the Medgar Evers Home Museum, we met with Minnie White Watson in the home where Evers and his young family lived and where he was assassinated in the driveway in 1963. He was field secretary for NAACP in Mississippi at the time, an activist for voter registration and social justice. One of the bullets came in through the living room window, went through the wall to the kitchen and made a hole in the refrigerator, which is still there.

There is a rich musical history in the South that was a recurring thread in our tour. At Malaco Records, also known as “the last soul company,” we were shown around by co-founder ‘Wolf’ Stephenson. Malaco is an independent record label where various blues and gospel acts have recorded over the last 50 years, including Dorothy Moore’s “Misty Blue” and the soundtrack for many movies.

We stopped by the Big Apple Inn, where fourth-generation owner Geno Lee told us the story of his activist great grandfather, who came to peddle hot tamales from Mexico City, and his Filipino mother, who was arrested as a Freedom Rider and threatened with the death penalty.

Freshly prepared “pig ear” sandwiches were passed around (sorry, no first-hand knowledge to report). Later, at the Mississippi Food Network, we met the woman who oversees the distribution of food and grocery products to more than 1.8 million people per year in the state, where the problem of poverty-related hunger is huge.

Had lunch at a local bar called Johnny T’s, with vintage black-and-white photographs lining the walls and an interesting talk by Robert Luckett, a white professor who teaches a history class on the Civil Rights Movement at Jackson State University.

Dinner at Frank Jones Corner (one of the few struggling businesses still open) included fried catfish and fried grits, followed by an impromptu blues performance by local musician, Jesse Robinson.

There was virtually no one out on the streets of Jackson, and hardly any stores, restaurants, or retail shops … even though it’s the state capital. All of us found this strange.

Tuesday - Indianola, Mississippi

The B.B. King Museum highlights the blues, which came out of the cotton fields, street corners and juke joints of the Mississippi Delta, and tells the story of Riley B. King, who is buried at the side of the building. People all over the world who couldn’t understand the words still loved the music.

Tuesday - Mississippi Delta

At the Museum of the Mississipi Delta, in Greenwood, we were met by Mary and Sylvester Hoover.

Mary Hoover, who owned a popular soul-food restaurant in the historically black Baptist Town neighborhood for nearly 30 years, prepared a lunch of barbequed ribs, her famous butter roll (think cinnamon bun), sweet potatoes, black-eyed peas, collard greens, and sweet tea. She helped out with the food scenes in the movie The Help and fed the cast and crew.

Sylvester Hoover, whose family members were sharecroppers here, is the proprietor of a combination grocery store and laundromat. He shares the history of this area with anyone who will listen, saying “I just want people to know about this place.”

Mr. Hoover took us on a brief walking tour of Baptist Town, where Morgan Freeman grew up and blues legend Robert Johnson died. While we stood inside of Hoover’s Store, his family’s multi-generational business, he told us stories of this close-knit community that was established in tandem with the local cotton industry.

We then drove with Mr. Hoover 20 minutes to a place called Money where the first marker on the Mississippi Freedom Trail was placed at the remains of the Bryant’s Grocery, where 14-year-old Emmett Till is said to have whistled at white shopkeeper Carolyn Bryant in August 1955. We heard details of how he was kidnapped, tortured, and killed. Emmett’s mother made sure his body was pulled from the river and shown to the world so that people could see for themselves the horror that helped jumpstart the Civil Rights movement. After 67 minutes of deliberations by an all-white jury, the two men who stood trial were acquitted. (They later sold their murder confession story to Look magazine.)

In Sumner, we sat in the courthouse where Emmett Till’s murderers were acquitted (even after being pointed out by a witness) and learned from two young residents about an apology resolution written by the community members of Sumner in 2015. Dinner at the black-owned Sumner Grille consisted of (guess what?) fried chicken.

Wednesday - Little Rock, Arkansas

At Little Rock Central High School we walked along the route where, in September 1957, an angry crowd of white people spit on and taunted members of the Little Rock Nine as they walked from the bus stop as the first black students to desegregate the all-white school. The historic building is beautifully maintained, and school was in session when we visited. Sitting in the auditorium, we heard about white kids throwing padlocks at black students, urinating in their lockers, flushing all the toilets so the black kids would be scalded in the showers, and much more … all while teachers and the supposed ‘guards’ looked away.

We also met with 77-year-old Ms. Elizabeth Eckford (the young girl with the sunglasses above in the iconic photo by Johnny Jenkins). We were told not to make loud noises around her because she continues to experience PTSD. She kindly spoke to us about the harassment she endured and why, after a year, she didn’t return to Little Rock Central High School and moved away. She asked us not to take her photograph.

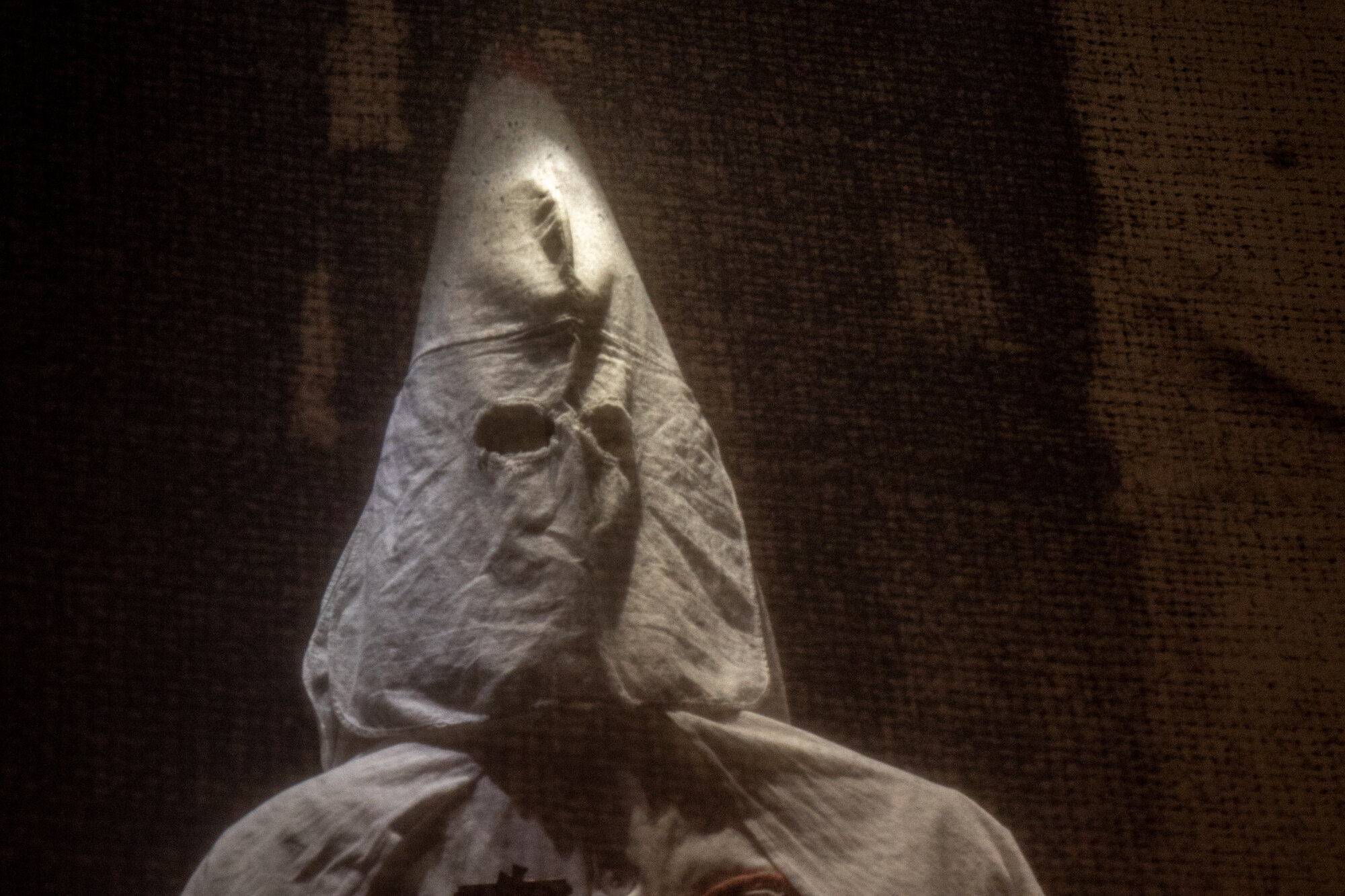

We stopped to visit the architecturally impressive William J. Clinton Presidential Center overlooking the Arkansas River. We had a lovely lunch there, none of it fried. We were supposed to meet up with Scott Shepherd at a BBQ dinner, but he couldn’t make it (because of his father’s recent passing). He is a former Grand Dragon of the Klu Klux Klan in Tennessee and now a ferocious anti-racism campaigner. That would have been fascinating.

Thursday - Memphis, Tennessee

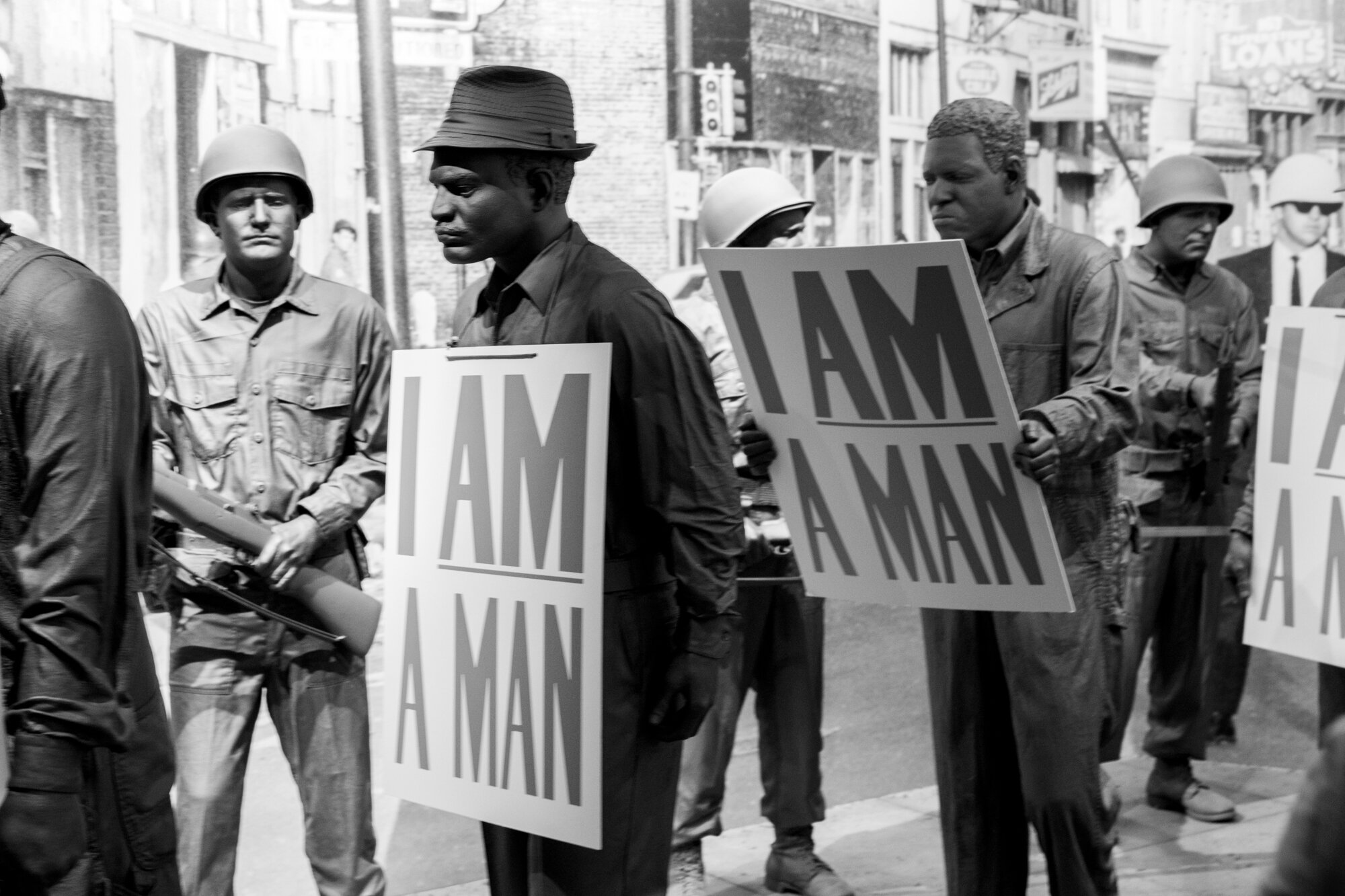

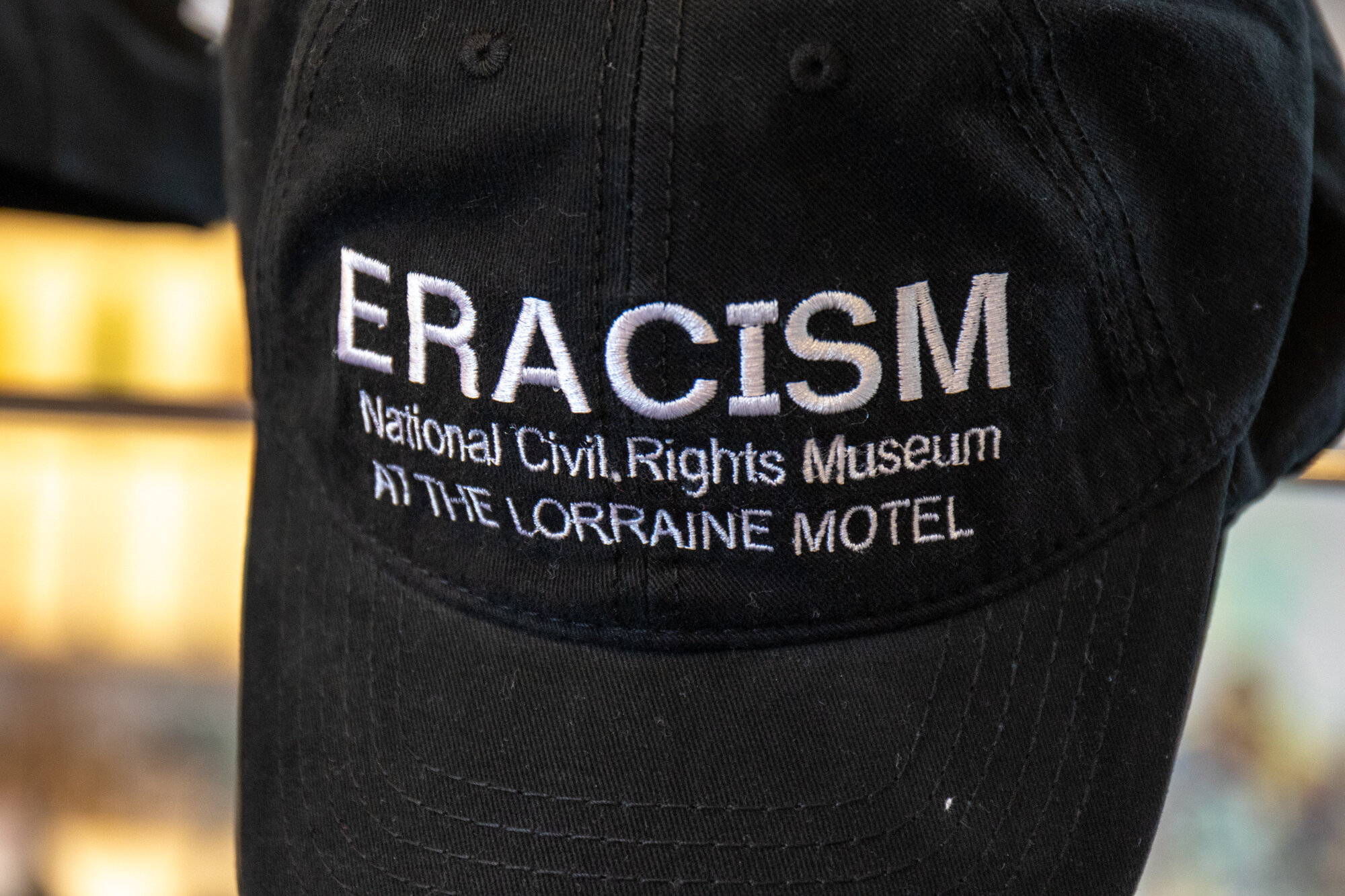

The tragically famous Lorraine Motel, which was once a safe haven for black travelers, is a place Martin Luther King, Jr. stayed at numerous times. He came in April 1968 to support a strike by sanitation workers. We got to see Room 306, from where he stepped outside to talk to friends in the parking lot below and was struck by a bullet in his neck. A large white wreath hangs on the balcony where it happened. The motel is now home to the National Civil Rights Museum, which includes the boarding house across the street from where the assassin’s shot was fired by James Earl Ray.

Before our visit to the Stax Museum of American Soul, we had lunch at the world-famous Gus’s Fried Chicken, which included more mounds of meat (which, as vegetarians, we did not eat), served with white bread and ketchup and lots of great sides, including cole slaw, fried okra, mac and cheese, and collard greens (which we did enjoy). The museum traces the history of the blues and its impact on American music. Before MLK was killed, white and black musicians were said to have gotten along. Afterwards, there were divisions.

One notable artifact in the Stax museum, positioned on a rotating stage, is the gold-plated Cadillac owned by Isaac Hayes. Built especially for the soul singer-songwriter in 1972 as part of his contract negotiation, it has a fur-lined interior, television, refrigerated bar, and 24-karat gold detailing on the exterior.

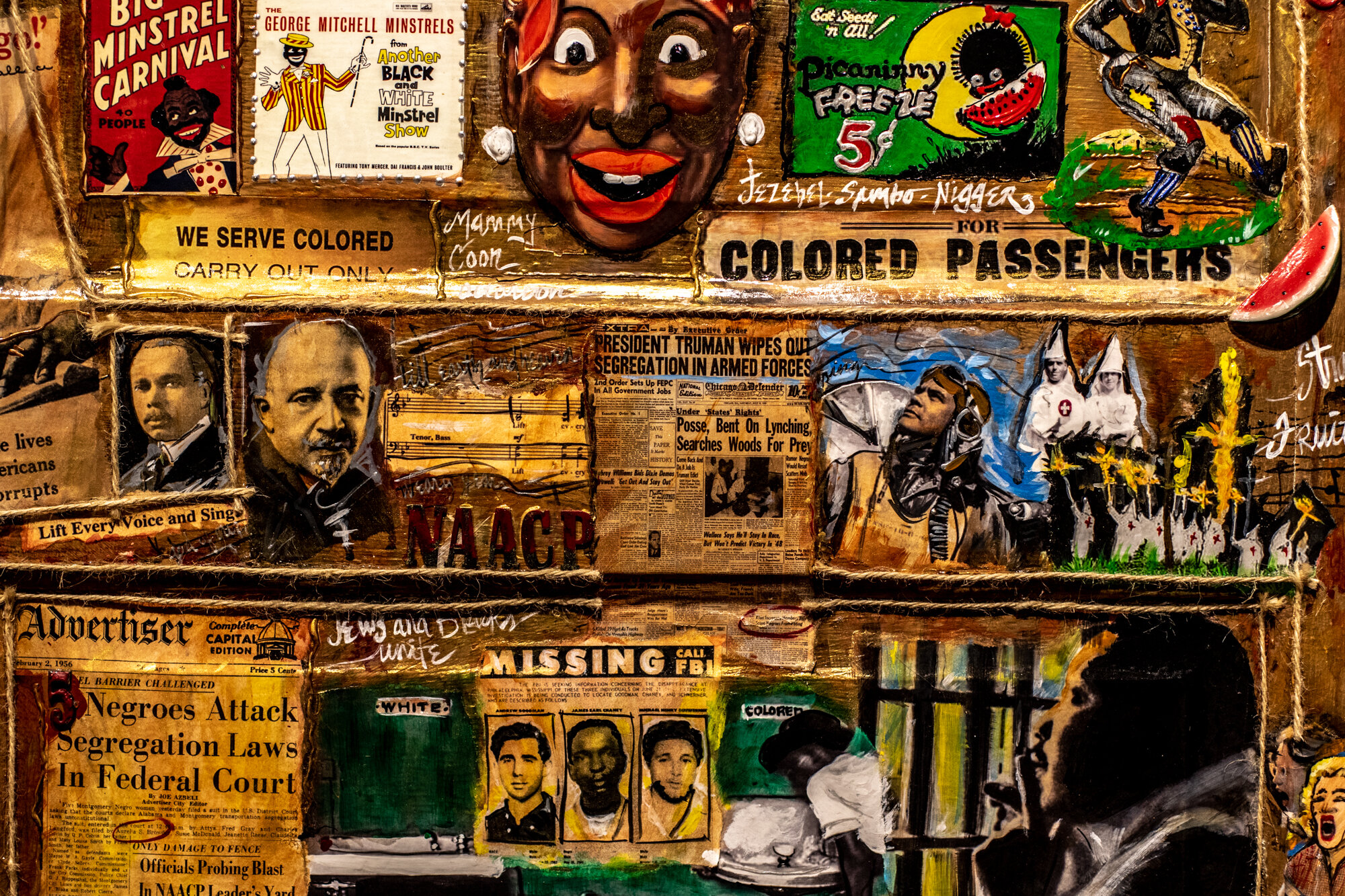

At the Slave Haven Underground Railway House, we stood in a modest home built by a slave sympathizer and German immigrant named Jacob Burkle. Along the walls were advertisements of “Negroes for Sale” and notices of rewards for those who had escaped. All 29 of us went down creaky steps into a dark cellar with a hidden passageway for runaway slaves attempting to flee north to freedom. We were directed to stow our cameras, put away our phones, and experience what it was like to hide in the dark. It was humbling and harrowing.

Friday - Birmingham, Alabama

In Birmingham, we met with Carolyn McKinstry at the 16th Street Baptist Church. She told us the story of when she was 14 and happened to pick up the phone in the church office when someone said “three minutes” and hung up. The subsequent bomb killed four young girls in the bathroom as they were preparing to sing in the choir. More than 8,000 mourners attended the funeral, but no city officials came. Ms. McKinstry later joined us for lunch at Delta Blues Hot Tamales (not recommend for those with acid reflux) and told us more about her life in Alabama.

Across the street, we walked through Kelly Ingram Park, where historic footage shows police attack dogs and high-powered hoses assaulting demonstrators, many of them children. On the bus, before we got there, we listened to a recent podcast (“Revisionist History”) discussing the accuracy of one of the sculptures in the park (pictured above).

Saturday - Selma, Alabama

At the Selma Interpretive Center, we met with Annie Pearl Avery, who joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at age 16. She talked to us about the many times she’s been arrested in the past 55 years (including three times in the 10 months before we all met her) and described her experience of walking across the Edmund Pettus Bridge during Bloody Sunday in 1965 (one of three tries).

Our walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge was led by a young woman named Michelle Browder, who had us singing protest songs, including “This Little Light of Mine” and “We Shall Overcome,” as we followed in the footsteps of the marchers. The 54 miles we then drove from Selma to Montgomery followed the marchers’ route; it took them five days, camping during the night in the fields of sympathetic farmers.

Sunday - Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery was the capital of the domestic slave trade in Alabama. At the waterfront, we witnessed a reenactment of a slave’s account and were asked to follow that woman, in single file, with one arm on the shoulder of the person in front of us as we walked in lock step as if in chains. Much like the underground railroad experience, I became immersed in the re-living of the slave trade. It’s hard to take a photograph when you’re being marched in virtual chains.

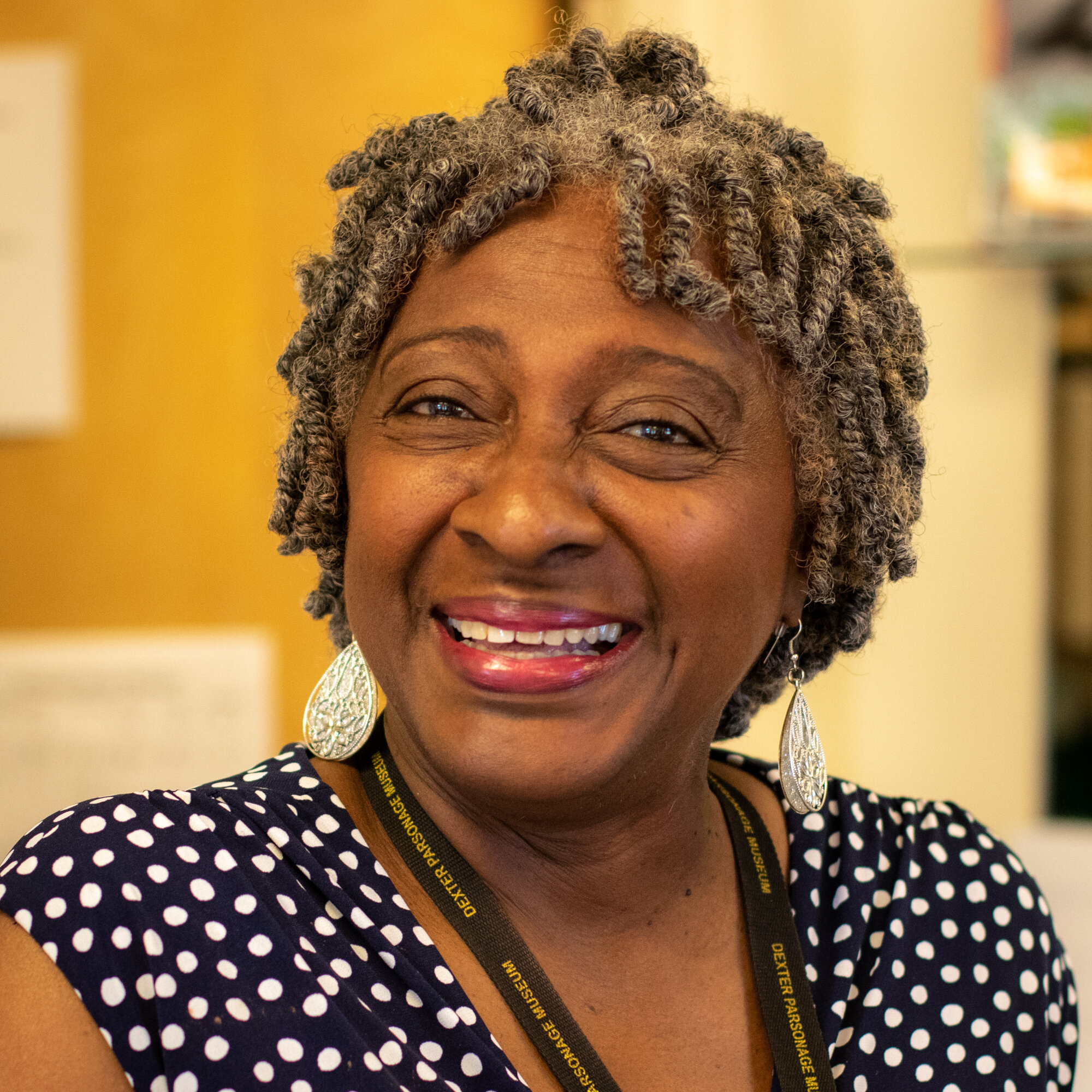

After a stop at the church where Dr. Rev. Martin Luther King served as minister, we toured the Dexter Parsonage Museum, the home of Dr. King and his young family from 1954 to 1960. Sitting in the kitchen of that home, we listened to a recording of Dr. King talking about not being able to sleep that night, having just received a phone call threatening to blow up his house and blow his brains out, if he didn’t leave town within three days. He recounted sitting in that very kitchen with a cup of coffee and hearing an inner voice telling him to stand up and not to falter. Three days later, his house was bombed.

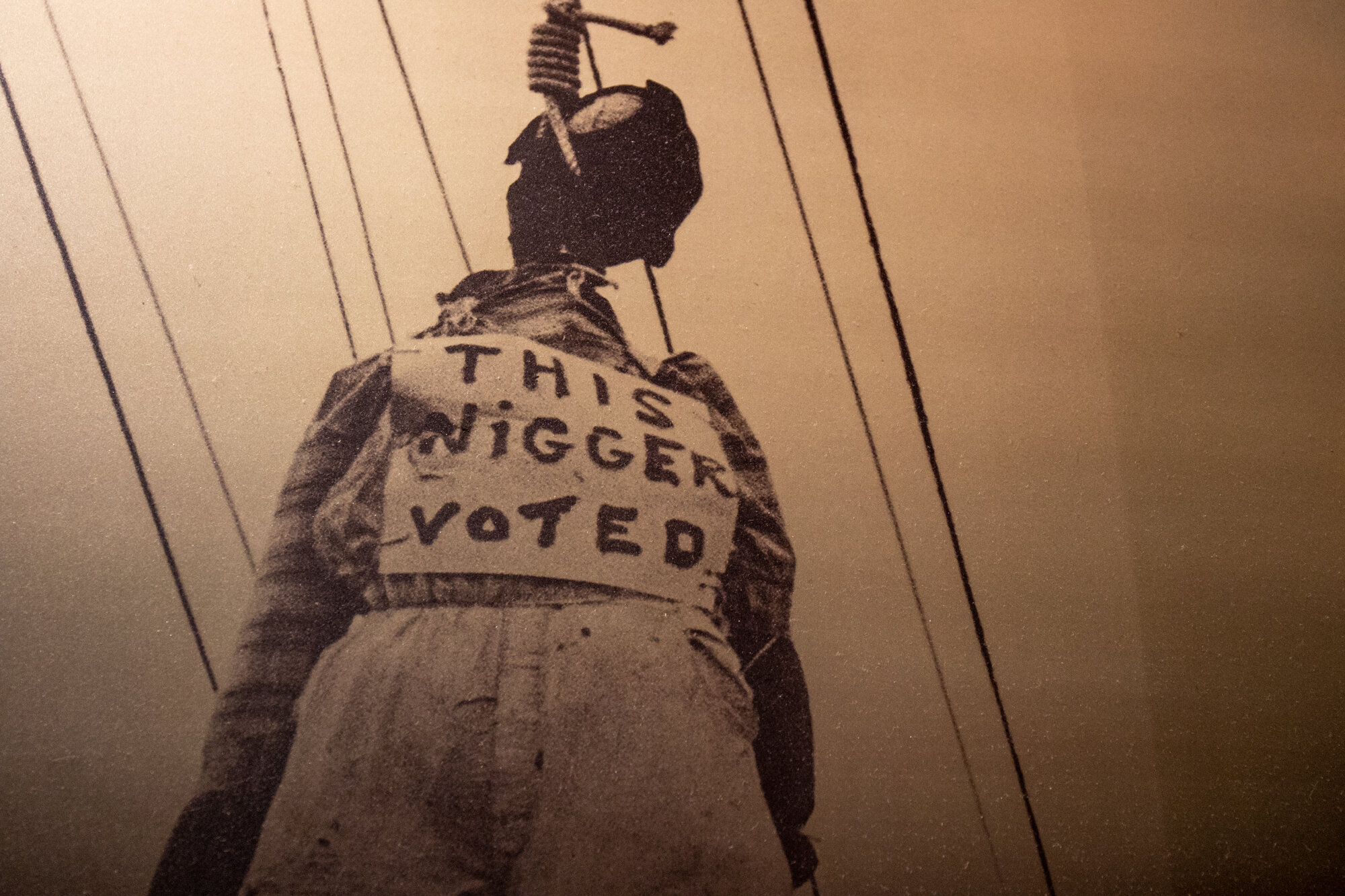

The newly opened National Memorial for Peace and Justice (created by the Equal Justice Initiative) is dedicated to the legacy of enslaved, terrorized, humiliated black people. People now call it the Lynching Museum, but founders didn’t think the memorial’s development would pass city and state approvals if named that overtly.

The memorial is a very powerful place, particularly the 800 steel monuments (one for each county) engraved with the names of victims, along with soil that was taken from these sites. Many lynchings attracted crowds of white families who came to watch and sometimes picnic near the spectacle. This is recent history; we were shocked to see 1949 as the date on one of the lynching monuments.

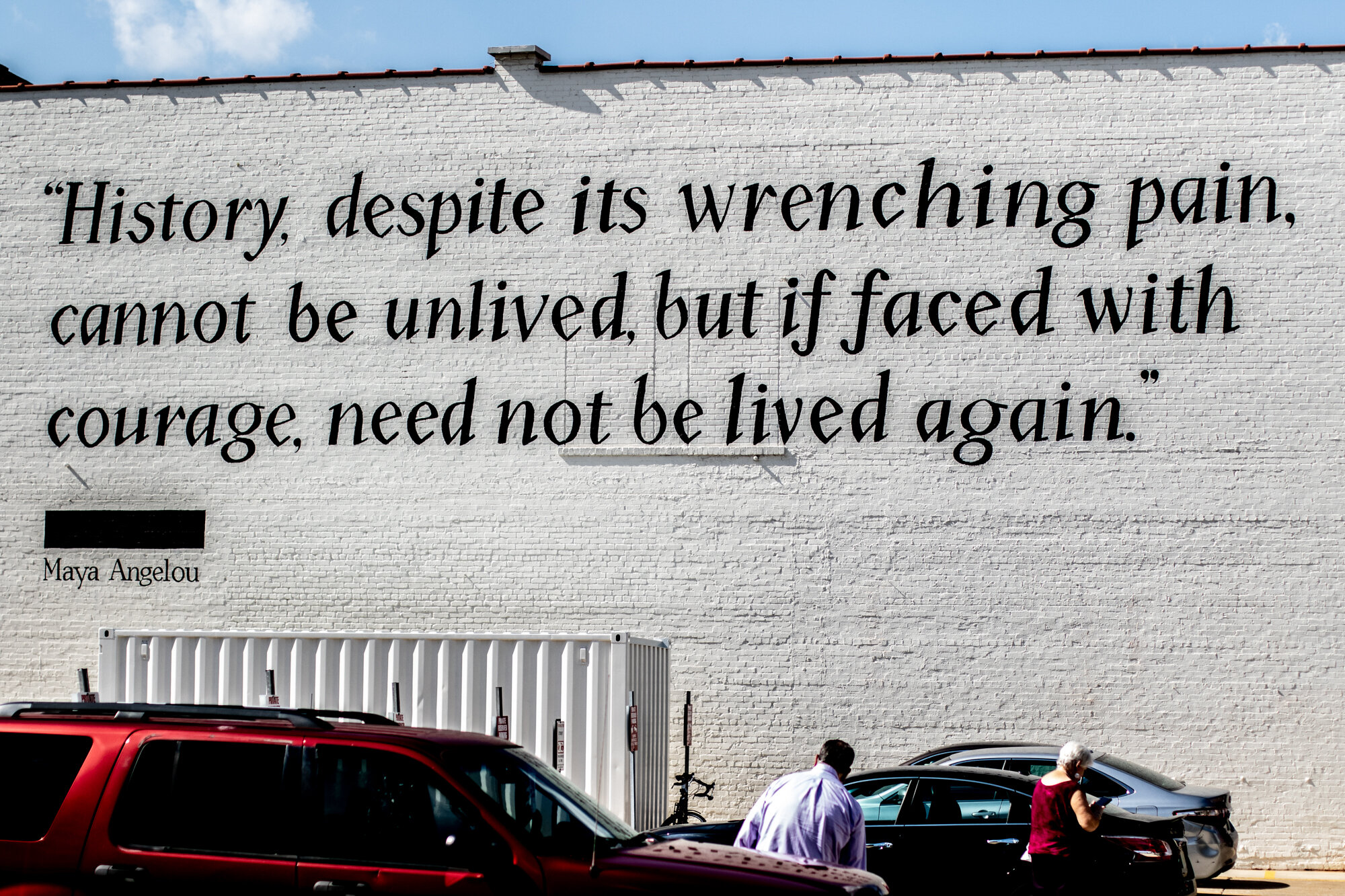

Later, at the Southern Poverty Law Center, which we and many others have supported for years in their work against hate and bigotry, we came across the names Howard, Jana, and Ari Wolff on a prominent donor wall in the museum that is next door to SPLC. The outdoor memorial designed by Maya Lin was closed for plumbing repairs, which is kind of ironic when you think of the inscription it features: “We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

The Legacy Museum is on a site where enslaved people were warehoused and sold -- one of the most prominent slave auction spaces in America. At this museum, created by Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), you can watch videos of inmates talking about what it’s like to be unjustly incarcerated and learn about the 3,000 children (tried as adults) currently serving life sentences. The photograph above of an actual underaged prisoner is just one of many exhibited that movingly illustrate the scourge of disproportionate mass incarcerations of young black men in today’s America. Little did I know just how resonant this imagery would become in the next year with the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement.

As part of EJI's Community Remembrance Project, they have a powerful display of jars of soil collected from lynching sites, creating a memorial that acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice. The only reason Bryan Stevenson himself didn’t join his three staff members who spoke with our group at EJI’s headquarters was that he was meeting in the office next door with Steven Spielberg (who toured the Legacy Museum when we did). I guess we’ll forgive him.

At several points in the tour, the group gathered for a debriefing with one of our two tour leaders, André Robert Lee, documentarian (The Road to Justice; Prep School Negro; I’m Not Racist, Am I?), educator, and consistently thoughtful gentleman.

At our final gathering, he asked us all to think about what we want to start, stop, and continue doing regarding social justice.

How would you answer?

For more of my images from this civil rights trip organized by The Nation, click through the slide show below.